The old Victorian house on Elm Street stood like a sentinel against the creeping fog of autumn evenings. Sarah had returned here after years away, the key turning in the lock with a familiarity that both comforted and unnerved her. The air inside was stale, heavy with the scent of dust and faded lavender, her mother’s perfume. She set her suitcase down in the foyer, the floorboards creaking underfoot as if protesting her presence.

Sarah was thirty-eight now, but in this house, she felt like the ten-year-old girl who had chased fireflies in the backyard with her father. Those memories were vivid: his laughter booming as he swung her high into the air, the warmth of his calloused hands. Her mother, elegant and distant, watching from the porch with a smile that never quite reached her eyes. They had been happy, hadn’t they? The family albums confirmed it—smiling faces, birthday cakes, Christmas trees glittering with lights.

But as she unpacked in her old bedroom, something felt off. The wallpaper, once patterned with roses, now peeled in places, revealing bare plaster beneath. She remembered helping her mother paste it up, their fingers sticky with glue, giggling over smudges. Yet, when she touched the wall, her fingertips came away with a faint red stain. Paint? Or blood? She shook her head, dismissing the thought. Jet lag from the flight, that was all. She needed sleep.

That night, dreams came unbidden. In them, her father wasn’t laughing. His face twisted in anger, veins bulging in his neck as he shouted, ‘You little liar!’ Her mother’s voice, shrill: ‘Why do you always ruin everything?’ Sarah woke sweating, heart pounding. It was just a nightmare, she told herself. Childhood wasn’t perfect, but it wasn’t hell either. There had been spats, normal family stuff.

The next morning, she ventured into the attic, seeking distraction in nostalgia. Boxes of keepsakes: her first bicycle helmet, school report cards, a porcelain doll with one eye missing. Then, the albums. Flipping through, she paused at a photo from her eighth birthday. There she was, blowing out candles, but behind her, her father’s hand rested on her shoulder—not gently, but gripping, knuckles white. Had it always been like that? She blinked, and the grip seemed to loosen in her mind’s eye. Trick of the light.

Downstairs, she brewed coffee, the machine gurgling like a distant memory. As she sipped, the phone rang— the landline, which she hadn’t even plugged in. No one had the number. Hesitant, she picked up. Silence, then a faint whisper: ‘Sarah… why?’ She slammed it down, pulse racing. Rats in the walls, maybe, or wind. But the unease lingered, a knot in her stomach.

Days blurred into a routine of unpacking and reminiscing. Yet cracks appeared. A neighbor, Mrs. Hargrove from next door, stopped by with a pie. ‘So glad you’re back, dear. After what happened… well, the house has been empty too long.’ Sarah frowned. ‘What happened?’ Mrs. Hargrove’s eyes darted away. ‘Oh, nothing. Just… your parents’ accident. Tragic.’ Sarah knew the story: car crash on icy roads, ten years ago. Both gone instantly. But Mrs. Hargrove added, ‘You were so brave, staying here alone after.’ Alone? Sarah had been in college, living in the city. Had she come back briefly? The memory was fuzzy.

That night, introspection turned to obsession. Sarah lit candles in the living room, sat cross-legged on the rug, and closed her eyes, willing the past to clarify. Breathe in, breathe out. Father’s voice echoed: ‘You’re my little girl, always.’ But overlaid, a darker tone: ‘Useless, just like your mother.’ No, that couldn’t be right. She opened her eyes to find a shadow in the corner, tall and imposing. It dissolved when she stood, but her reflection in the window showed hollow cheeks, eyes wild. Am I losing my mind?

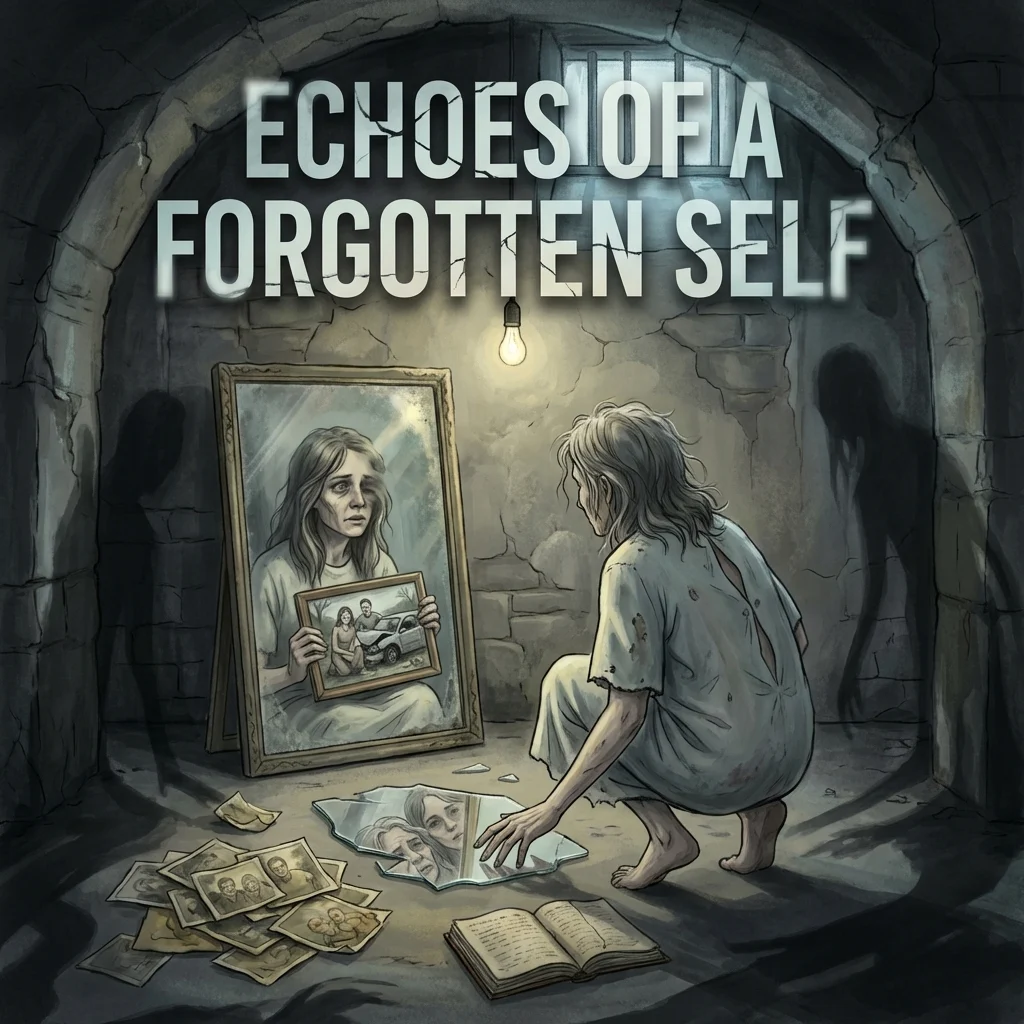

She began journaling, pen scratching furiously. ‘Day 5: Memories conflicting. Recall father teaching me to ride bike—joyful. Then, pushing me off, laughing as I fell, skinning knees.’ Which was true? The bike incident: in one version, triumph; in another, humiliation. Her mother’s hugs: tender or suffocating? Sarah’s hands trembled. Perhaps early dementia, like Grandma. Isolation wasn’t helping; she should call a friend.

But the phone lines seemed dead now, and her cell had no signal. The house felt smaller, walls pressing in. Paranoia crept: was someone watching? Footsteps overhead at night, though attic empty. She barricaded the bedroom door with a dresser, lay awake listening to her heartbeat.

One afternoon, rummaging in father’s study, she found a locked drawer. Pry bar from garage—inside, letters. Handwritten, her mother’s script: ‘Dear Sarah, I know what you did. The bruises aren’t from falls. He’s protecting you, but I see. Please, stop before it’s too late.’ Bruises? Sarah’s stomach churned. She had been clumsy as a kid, always falling. But the next letter: ‘Last night again. Your father’s arm—broken? Call the police.’ This made no sense. Her father had never hurt her; he was the victim?

Memories surged: a fight, plates shattering. Sarah, small, grabbing a knife? No, that was absurd. She was the child. Tears streamed as she rocked on the floor. ‘What’s real?’

Tension peaked as nights grew longer. Shadows morphed into figures: father looming, mother weeping. Sarah screamed at them, ‘Leave me alone!’ But they whispered truths she dared not hear. In mirror, her face aged, lines deepening unnaturally. Time losing meaning.

On the tenth day, desperation led to the basement—never ventured before, door always locked. Key from mother’s jewelry box. Dank stairs descended into gloom. At bottom, a room: hospital bed, monitors silent, photos pinned to walls— all of Sarah, but younger, happier. No: the girl in photos was her, but captions: ‘Patient E. Thorne, catatonic since 1995.’

Heart hammering, she approached a dusty mirror. Her reflection stared back—not thirty-eight, but sixty-five, frail, eyes vacant. No: the woman in mirror moved independently, smiling cruelly. ‘Hello, daughter.’

Flash: real memory. Sarah wasn’t the daughter. She was Eleanor, the mother. The ‘childhood’ memories were her daughter Lily’s life, stolen in grief. Twenty-five years ago, Sarah—no, Lily—had died in car crash caused by Eleanor’s drunk driving. Husband too. Guilt fractured her mind; she became ‘Sarah,’ the innocent girl, reliving fabricated purity in delusion. The house? Sold long ago; this was a psych ward room, her ‘home’ in endless loop.

Nurses entered—no, hallucinations solidified. Real voices: ‘Eleanor, time for meds.’ She—no, Eleanor—clawed at the air, screaming denials. But truth crashed: every ‘memory’ recontextualized. The loving father? Her husband, beaten in rages. The happy girl? Lily, abused unknowingly until fatal night.

Eleanor collapsed, whispers fading. In final clarity, peace: guilt buried no more. Lights dimmed; end of loop.